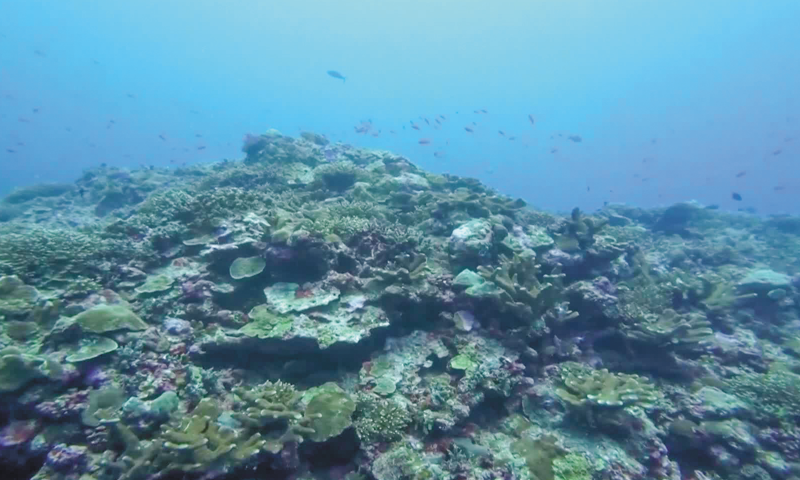

The coral reefs in the Huangyan Dao national nature reserve located in Sansha, South China's Hainan Province Photo: IC

Editor's Note:

The activities of the Chinese people in the South China Sea date back over 2,000 years. China is the first to have discovered, named, explored, and utilized the maritime resources on and around Nansha Qundao and other relevant waters, and the first to have continuously, peacefully, and effectively exercised sovereignty and jurisdiction over them. Silent archaeological relics are faithful witnesses to this.

The Global Times is launching the series "Artifacts Tell South China Sea Truth." Through historical relics, maps, and other materials from ancient and modern times, both at home and abroad, the evidence will show how China's territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the South China Sea have long been clearly recorded and recognized by world history. This is the third installment in the series, demonstrating that Huangyan Dao has been China's inherent territory since ancient times through Philippine maps, documents from the international community, and China's verifiable historical records.

China released the baselines of the territorial sea adjacent to Huangyan Dao in the South China Sea on November 10, 2024. The Chinese government delimited and announced the baselines of the territorial sea adjacent to Huangyan Dao, which is a natural step to lawfully strengthen marine management and is consistent with international law and common practices, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson said on the day.

However, in recent years, the Philippines has persistently made illegal claims to Huangyan Dao, disregarding historical facts. How did the Philippines gradually attempt to unlawfully incorporate Huangyan Dao into its territory? What does history reveal about China's ownership of Huangyan Dao? The Global Times has uncovered answers from historical maps in historical China, the US and the UK, and archaeological documents recording China's surveying and mapping the Huangyan Dao, shedding light on the historical context of Huangyan Dao's ownership and the fact that the international community has never recognized the Philippines' claim to it.

Philippines' ambitions to encroach on Huangyan Dao

Public records show that the modern boundaries of the Philippines were defined by three international treaties: The Treaty of Peace between the United States of America and the Kingdom of Spain (1898), the Treaty Between the Kingdom Spain and the United States of America for Cession of Outlying lslands of the Philippines (1900), and the Convention between the United States of America and Great Britain delimiting the boundary between the Philippine archipelago and the State of North Borneo (1930). None of these treaties included Huangyan Dao within the Philippines' territorial scope. In 1935, the Philippines' constitution explicitly excluded Nansha Qundao and Huangyan Dao from its territorial boundaries.

At the time, the international community did not recognize Huangyan Dao as part of the Philippines. In 1902, the US Congress approved the publication of the Pronouncing Gazetteer and Geographical Dictionary of the Philippine Islands, United States of America, with maps, charts, and illustrations, which marked Huangyan Dao and the entire South China Sea islands as being outside the Philippines' boundaries. In 1938, during discussions with the Philippine Commonwealth government about Huangyan Dao, US secretary of war Harry Woodring stated that Huangyan Dao lay outside the Philippines' boundaries, according to United States Government Publishing Office.

In fact, for a long period after World War II, the Philippines did not claim sovereignty over Huangyan Dao. In 1968, the Philippines passed Republic Act No. 5546, which still explicitly placed Huangyan Dao outside its territory.

It was not until the discovery of an ancient map that the Philippines' ambitions toward Huangyan Dao surfaced. In 1734, Spanish Jesuit priest and cartographer Pedro Murillo Velarde (1696-1753) and others drew the Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas (Hydrographic and chorographic map of the Philippine Islands), which included a geographical mark resembling Huangyan Dao. The map showed three reefs off the western coast of Luzon, with the middle one labeled "Panacot."

This annotation prompted the Philippines, starting in the 1990s, to assert sovereignty over Huangyan Dao, claiming that "Panacot" referred to it. However, this map, drawn 18 years later than official Chinese maps, does not alter the historical ownership or sovereignty status of Huangyan Dao. In fact, this claim is entirely a misunderstanding, Chinese scholars found after research.

"Panacot" is not Huangyan Dao. From 1792 to 1805, British and Spanish expeditions conducted surveys of the reefs on old maps and confirmed that "Panacot" was mistakenly included and does not exist in reality. Consequently, it was removed from subsequent maps. Nevertheless, in May 1997, the Philippines abandoned its previous stance and formally claimed territorial rights over Huangyan Dao. In 2009, the Philippine Senate passed Republic Act No. 9522 that defines the baselines of the Philippine, which, for the first time, illegally included Huangyan Dao within the Philippines' territory.

The "Genglu Bu" (Navigation Route Book), a navigation manual used by Hainan fishermen since the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), records five routes to Huangyan Dao Photo: Courtesy of China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

Ancient records confirm Huangyan Dao belongs to China

In the vast South China Sea, islands and reefs are scattered like stars. Among the Zhongsha Qundao, nearly all reefs are submerged, with Huangyan Dao being the only one rising above the sea, shining like a radiant pearl.

Over 700 years ago, during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) in Chinese history, Emperor Kublai Khan (the first Yuan Dynasty emperor) ordered a nationwide territorial survey. Surveyors were dispatched to establish 27 astronomical observation stations, with the southernmost point being Huangyan Dao, as recorded in Yuan Dynasty historical documents.

After the establishment of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), to regulate merchant ships traveling to China's surrounding waters, authorities organized efforts to map the South China Sea routes, including Huangyan Dao. During this period, maps drawn by officials are believed to feature early depictions of Huangyan Dao, Chen Xidi, a researcher from China Institute for Marine Affairs at the Ministry of Natural Resources, told the Global Times.

In 1901, the book "Chronicle and Geography of China river and sea sites with strategic significance" clearly marked Huangyan Dao. This book is an abridged translation of the third edition of "China Sea Directory" by the British Navy in 1894, Chinese archaeologists have discovered. The second attached map in the book, marks the Chinese transliteration of "Scarborough Shoal." Scholars found through data review that although the map did not indicate that Huangyan Dao belongs to China by means of lines, colors, or text labels, in the concept at that time, the South China Sea was China's maritime territory, which was recorded in many documents, and the islands in the sea naturally belonged to China.

Official academic data shows that in 1935, in order to more accurately mark and manage the South China Sea islands, the government of the Republic of China sent personnel from multiple official institutions such as then Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Navy Ministry, and the Ministry of Education to form a professional land and water map review committee. After a detailed investigation, the committee released the "Chinese-English name list of islands in the South China Sea of the Republic of China," announcing 132 place names in the South China Sea, among which Huangyan Dao was named "Scarborough Shoal."

By 1947, the government of the Republic of China further refined and improved the naming and management of the South China Sea islands. The government updated the name list and announced 172 place names in the South China Sea. Among them, Huangyan Dao was given a new name - "Minzhu Jiao" and was officially included in China's Zhongsha Qundao, Chen noted.

In 1983, the then Chinese toponymy committee was authorized to announce "some standard place names of China's South China Sea islands," in which Huangyan Dao was used as the standard name, with Minzhu Jiao as the auxiliary name, according to a report by the People's Daily in May, 2012.

China's continuous jurisdiction over Huangyan Dao

In fact, ancient China not only carried out official surveying and mapping activities on Huangyan Dao and its surrounding waters, but also had folk fishery development. In the eyes of fishermen in Tanmen, South China's Hainan Province, the waters around Huangyan Dao are seas where they have worked for generations.

The "Genglu Bu" (Navigation Route Book), a navigation manual used by Hainan fishermen since the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), records five routes to Huangyan Dao, reflecting the historical facts of Hainan fishermen's navigation and production in the area.

After the founding of the People's Republic of China, the Chinese government has conducted scientific investigations on Huangyan Dao many times. In 1977 and 1978, researchers from the South China Sea Institute of Oceanology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, landed on the island twice; in 1985, the South China Sea branch of the State Oceanic Administration organized an expedition to land on the island; in 1994, a Chinese scientific expedition team in the South China Sea landed on the island and built a 1-meter-high cement monument on it, reports show.

In 1994, 1995, and 1997, Chinese authorities approved three separate expeditions by radio enthusiasts to conduct amateur radio activities on Huangyan Dao. To support these expeditions, the American Radio Relay League agreed to China's proposed radio call sign for Huangyan Dao. In 2007, a 16-member team of radio enthusiasts, under the call sign BS7H, applied to China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs for permission to conduct an expedition to Huangyan Dao. The approval of this expedition marked international recognition of Huangyan Dao as part of China.

The Philippines once claimed that Huangyan Dao is closest to it and should "belong" to the Philippines, which once confused the international community. But in fact, there is no international law principle that determines sovereignty based on geographical proximity, Chen said.

Li Guoqiang, deputy director of the Chinese Academy of History, once said that there are two important bases for demonstrating territorial acquisition: One is legal basis, and the other is historical basis, and both are indispensable.

Chen emphasized that China's sovereignty over Huangyan Dao has sufficient historical and legal bases, which are far earlier than any claims put forward by the Philippines or other countries. Since the Yuan Dynasty government surveyed Huangyan Dao, the island has always been an inalienable part of China. It has not only witnessed China's official surveying, mapping, and naming but also the fishing production of Chinese fishermen.

Looking forward to the future, Huangyan Dao, this bright pearl, will always stand in the vast blue waves of the South China Sea as China's sacred territory. History will eventually tell people who the only true owner of Huangyan Dao is, said Chen.

Facts speak louder